- Home

- Laura Thalassa

War (The Four Horsemen Book 2) Page 16

War (The Four Horsemen Book 2) Read online

Page 16

I want to shrug the statement off. I might’ve even a few days ago. But for whatever reason, today, that explanation hits me low in the gut.

“Wow, I’m flattered.” I try to sound mocking and irreverent, but I don’t quite pull it off.

War gives me a pained smile, like the effort of abstinence hasn’t been without its challenges. The poor wittle horseman and his neglected dick. What ever will he do?

“What if I never sleep with you?” I ask.

“I have been inhuman for a long time, Miriam. I can manage my body well enough until I am inhuman once more.”

Shivers. I knew he wasn’t truly human, but hearing him say it is a whole lot more sobering than just generally being aware of it.

“You, on the other hand,” he continues, “have only ever been human, and you are bound to your most basic nature. We will see how long you last, wife.”

Today of all days, that statement finds its mark.

Out on the open road, there’s no mistaking that I am living in a terrible time. The most obvious sign of it are the bodies. Just like the first time I traveled with War, we pass by several of them. They’re bloated and stinking, and scavengers have already mutilated them. They lay out in the street, or half in, half out of residences. I’m sure there are more dead cooped up in houses, rotting away amongst all their worldly possessions.

Scattered near the bodies are piles of bones, and I know that War’s zombies are responsible for this.

But it’s not just the bodies.

We pass by Ashkelon, the city south of Ashdod. This place, too, has been sacked. Some of the buildings still smolder in the distance, and there’s a stillness to the air that feels utterly devoid of human life.

Even once we pass by the city, there are still strange sights that I would never have seen a decade ago. Out here, in between towns, our surroundings are speckled with junkyards and scrap metal. The carcasses of old cars and electronics and other useless technology sit abandoned along the side of the road.

I don’t know if the sight of all this old decadence and waste will ever stop being jarring to me. I’ve sifted through so many junkyards over the years, but even after visiting hundreds of times, I am still not immune to the prickling sensation up my back, like there are old ghosts about.

“Can you tell me about your brothers?” I ask, my eyes lingering on a rusted out dryer and a stained fridge we pass by.

“They are lethal and terrible just like me,” War says.

Even in the sweltering midday heat, the hairs on my arms rise.

“Where are they?” I ask.

“Where they need to be,” he replies cryptically.

“Even Pestilence?” I press. War had mentioned that the first horseman had been stopped.

The horseman curls his upper lip a little. His silence has my heart speeding up. “Where he is, is no concern of mine. His purpose has been served.”

I think … I think that’s War’s evasive way of saying his brothers really can be stopped.

Now I need to figure out how.

“When will Famine come?” I ask.

“When it is his time.”

“And … when is that?”

War shakes his head, squinting off in the distance. “After I have made my final judgment.”

“Your final judgment?” I say. “Of what? Humans?” I raise my eyebrows.

War turns his head and gives me a long look.

Yes, of humans.

“Why do you think we’re here?” War says.

I stare back at him. “Why don’t you tell me?” He’s the one with all the answers.

“Your kind has not been made wrong,” War says cryptically, “but you have all collectively chosen wrong.”

I’m trying to follow War’s words and how they tie into judgment, but I don’t really know what he’s trying to say. That human nature itself is fine, we just turned evil somewhere along the way? And now he has to punish us for it?

“And so we’re all to die?” I say.

“You’re being called home.”

What he means is that humankind is being swept up into God’s trashcan like bad leftovers.

“And there’s nothing you can do about it?” I ask. I don’t know why I bother. War hasn’t shown one iota of interest in actually saving humankind. He’s completely fine annihilating us.

“Miriam, it isn’t for me to do anything. Men are the ones who must change. I merely judge their hearts along the way.”

I run a hand through my dark brown hair. “How can you even judge us if you’re too busy hacking away at us all?”

War’s face is grim. “There’s an order to what I and my brothers do.”

“What does that even mean?” He’s dancing around my questions.

“Four calamities, four chances.”

An unwelcome tingle of fear slips down my spine. “Four chances for what?”

His eyes fall heavily on me. “Redemption.”

Chapter 23

Redemption. That word weighs heavy on me that night as I stare up at the sky. Humankind has been so dead-set on stopping the horsemen that we’ve overlooked one simple truth: maybe it’s not the horsemen that need to be stopped.

Maybe it’s us.

Not our lives—though War would insist differently—but our actions. Technology was stopped in its tracks the day the horsemen arrived. But if it was the things we created that were wrong, that single, obliterating act should’ve been it.

And it wasn’t.

Pestilence surfaced five years after that. Five years. And now it’s been well over a decade since the horseman’s initial arrival. Why the wait? What are we missing?

I remember the sight of my three surviving attackers, all waiting to die. I remember looking at those men, being so sure they would hurt someone again if they were freed. I didn’t want to believe it—I still don’t—but I thought it all the same.

Somehow we’re all supposed to redeem ourselves. I’m just not sure we’re all willing to.

And so we’re slated to die.

We pass through Gaza, the entire strip of it. No one remains. It’s just as abandoned as Ashdod and Ashkelon. Bodies rot under the summer sun, and the deep, foreboding hum of swarming flies raises the hair on the back of my neck.

Jabalia, Khan Yunis—all the cities within the strip look the same.

Dead.

“What have you done?” I whisper as I take it all in.

“I couldn’t leave you,” War says.

I glance over at him.

“When you were injured,” he clarifies.

Horror dawns on me. While he stayed at my side and mended me, he was still killing.

War meets my gaze, and there’s no remorse in his pitiless expression. He’ll have it all—me and the end of the world. It’s his birthright to take it all.

I look away. To think I was fantasizing about him only a day ago …

My attention returns to the ruins of this civilization. I didn’t even know the army raided this far from their basecamp.

Only, the more I look at the carnage and the more I think about it, the more I come to believe that War’s army didn’t move this far south. There are no smoldering buildings, there are no fallen soldiers. There’s nothing to indicate man met man on the battlefield and each fought the other to the death.

But there are piles of bones. Lots and lots of bones.

“You used the dead?” I ask.

His only response is to meet my eyes and say again, “I couldn’t leave you.”

I don’t speak to War after that. Not for hours and hours.

Unfortunately, he seems perfectly fine with that arrangement.

It’s not until the sun is setting and War is steering his steed off the road and towards a deserted outpost that he says, “I know you’re angry with me.”

I shake my head. “I’m not angry with you,” I say. I can feel his gaze on me. “I’m angry at myself.”

War swings himself off Deimos an

d takes the reins of my own horse, leading the creature to a set of troughs filled with old feed and murky water.

I glance around. We’re in the middle of nowhere. Truly. Outpost aside, there’s nothing here but road and barren, sun-bleached earth.

“A week ago, your people brutalized you,” he says, “and still you think they should be spared?”

I ignore him, sliding off Lady Godiva and wincing at my aching legs.

He ties my horse’s reins and returns to my side.

“Answer me,” he demands. For once his eyes are angry, and I get the impression he’s remembering the night I was attacked.

“Why?” I say. “Reasoning with you accomplishes nothing.”

War steps in close. “And if it did?” he asks softly. “If I listened to you and tried to change, what then?”

I search his face. Everything about him is brutal—brutal beauty, brutal power, brutal personality.

“I think you know what would happen if you tried to change,” I say, lifting my chin a little.

I’m having a difficult enough time keeping my hands off War as it is. If he did give me a reason to believe he was capable of changing for the better, I might be tempted to sully his good name right here, right now.

The horseman’s gaze drops to my lips and his eyes noticeably heat. “And if I did this, if I … changed—would that make you less ashamed of the fact that the world hates me yet you are mine?”

“I am not yours.” There’s a very big difference between wanting to fuck a pretty man versus being his.

The corners of War’s sinful lips curve upwards. “You are mine. You knew it the moment you stared up at my face that day in Jerusalem. Just as I knew you were mine then too.” His gaze drops to the hollow of my throat, where my scar is.

War steps in closer, drawn by my old wound. “Mine by violence. Mine by might. Mine by divine proclamation.”

I think he might kiss me. He has that intense look on his face like he wants to, and he’s made it perfectly clear that he believes I am his in every sense of the word.

But instead of leaning down and pressing his lips to mine, he brushes past me and begins to set up camp.

I stare at his back as he works. Why doesn’t he just seal the deal? He’s strong enough, and he has no problem overpowering innocent humans on the battlefield. Why draw the line when it comes to his unwilling “wife”?

“What would you change about me?” he asks over his shoulder, interrupting my thoughts.

Whatever it is that drives you.

“Stop killing people,” I say.

He pauses in his work. “You would have me surrender my purpose?”

Yes. But that’s clearly too much to ask of him.

I walk over to him, grabbing the other end of the pallet he’s unfolding and help him spread it out.

“At least save the children,” I say.

War brushes my hands away, and for a guy that isn’t really a guy at all, he sure seems to know a bit about chivalry or whatever it is he thinks he’s doing for me.

“Children grow up,” he says, “and tragic childhoods make the most vengeful of men.”

Men who would try to stop War … if he could be stopped at all.

I think of my own childhood. Of sitting on my father’s lap and listening to him tell stories of faraway places and people he’d known. I remember being in the kitchen, making challah with my mom, the family recipe supposedly passed down over hundreds of years before I came to learn of it. I remember how peaceful, how loving, my childhood was.

At least, that was how it was before.

After …

I close my eyes and I can hear the grinding smash of metal the day the horsemen arrived. The day my father died. And then, years later—

The water rushes in—

I can feel its icy chill, squeezing the life out of those memories.

The horseman is right. It’s hard to remember what you loved without also remembering what you hated.

“Besides,” War continues, unaware of my own thoughts, “children become adults, who then beget more children.”

Problematic when you’re trying to kill off a species.

War finishes setting up the pallet, then pulls out a few logs of wood from my horse’s pack, along with a weathered packet of matches and some kindling.

“Doesn’t that bother you? That children are dying?” I ask, taking a seat on one of the pallets. “Surely there’s some part of you—maybe the part that saved me—that’s bothered by that.”

The horseman begins stacking the dry wood. “Famine takes no issue with children—and Death,” a mirthless smile flashes along War’s face for a second, and then it’s gone. “Death would love nothing more than to hold the entire world in his cold embrace.

“So, no, Miriam, I am not concerned with my leniency.”

“What about Pestilence?” I press, slinging my arms over my knees.

“What of him?” War finally says, adding the kindling to the logs.

My heart pounds harder and harder. There’s something here. Something to this first brother that War decidedly doesn’t want me to know.

“You didn’t include him in your list,” I say.

War takes his time lighting a match, then bringing it to the kindling.

“Did I need to?” he says, snuffing the match out. “You and I both know that the plague doesn’t discriminate its victims.”

I narrow my eyes on War, sure that he’s being clever with his words. “Whatever it is you’re keeping from me, I will find out.”

Late that evening, after I have eaten and drunk my fill (War abstaining in the name of rationing resources), I watch the horseman over the dying fire. He has his sword across his lap and a whetstone to sharpen its blade. I can hear the rhythmic zing of it as he slides the stone along the metal.

“Tomorrow we will set up camp here,” he says, shattering the quiet.

“Here?” I ask, glancing around. We’re in the middle of nowhere. “Where even are we?” I ask.

“Egypt,” War replies.

Egypt.

I’ve never been out of the country before. It feels weird, traveling farther than I ever have before. For years I’ve wanted to travel; go figure that when I finally get the opportunity, it’s in the wrong direction.

My gaze sweeps over our barren surroundings again. So this will be the end of our travels. Not that it means anything. The horseman will erect my tent right next to his and we’ll continue right on with this thing we have between us.

But this is the end of something, at least for now. Out on the road it’s easier to like a man like War. He’s not focused on killing people, and honestly, when you remove that from the equation, he’s not nearly so horrible.

The low flames flicker over his olive skin and dance in his eyes. They glint across the blade of his sword and lovingly illuminate his thick arm. War doesn’t look like a modern man right now.

“Before you arrived on Earth, who were you?” I ask.

His eyes meet mine. “Not who, Miriam,” he says, “but what.”

I don’t say anything, and eventually he continues.

“I have lived along the Somme, rested Normandy, and scattered myself on the ancient shores of Troy; I have tasted most parts of this earth, and my dead have sowed countless fields with their bodies. Even now I can feel those bodies deep beneath me in the soil.”

Goosebumps break out along my skin. Half of what he’s saying doesn’t make sense, but I can feel the truth of it. Every last word.

“I’m old and new and it is a terrible, burdensome experience.” Zing. He passes the whetstone over his sword again.

“But unlike my brothers, I am unique in one single, fundamental way.” He pauses, his gaze heavy on mine.

“What way is that?” I ask, even though I’m not sure I want to know the answer.

His eyes go to the fire. “I exist solely in the hearts of men.” War gazes at the flames. Now that I’ve opened him up, it seems as t

hough his entire story is tumbling out. “All creatures can experience pestilence, famine, and death—but war, true war, that is a singularly human experience.”

As I stare at him, his face mostly eclipsed in shadow, realization dawns.

“That’s why you judge men’s hearts,” I say. Because War, borne of human strife, is the only one of the horseman to truly understand our hearts and our hearts alone.

War laughs, setting the whetstone and his sword aside. “All my brothers judge men’s hearts,” he leans forward, “it’s just that I happen to know their hearts. I have resided in them for a long, long time, wife.”

Again, a chill slides over me. War’s gaze is far too intense, and what he’s saying is making me feel like reality and the unknowable are actually separated by a thin curtain, and right now, the horseman is drawing that curtain aside.

On a whim, I move closer to him.

He doesn’t know anything beyond war. That’s been the entirety of his existence up until now.

Reaching out, I capture his hand between mine. I don’t know what I’m doing, only that the glow of his knuckle tattoos look like fireflies caught between my hands.

Immediately, War’s gaze moves to mine, and his fingers tighten.

“If you know men’s hearts,” I say, threading my fingers between his. What am I doing? “then you must also know that most men don’t want to fight.”

It’s countries and causes and kings that want war, and soldiers who pay the price for it.

“Are you really so sure of that, Miriam?” But for once, War is the one who sounds like he doesn’t want to fight.

I run my finger over his knuckles, tracing each glyph. “I am.”

I still have no idea what in God’s name I’m doing, but I know that War won’t stop me.

He’s been wanting us to touch for a lot longer than I have.

He stares at the action, his eyes deep, his body unusually still.

My finger slips over the back of his hand and up his tan forearm, beginning to touch all the skin I’ve told myself not to touch. Beneath my fingertip, I can feel the thick bands of his muscles. Muscles that, to the best of my knowledge, formed into existence a little over a decade ago.

“Wife.” War’s voice has gone rough with want, and there are a thousand desires in his eyes. He’s starting to lean forward, and he looks like he’s going to pounce on me at any second.

Pestilence (The Four Horsemen Book 1)

Pestilence (The Four Horsemen Book 1) War (The Four Horsemen Book 2)

War (The Four Horsemen Book 2) Famine (The Four Horsemen Book 3)

Famine (The Four Horsemen Book 3) The Queen of Traitors (The Fallen World Book 2)

The Queen of Traitors (The Fallen World Book 2) The Unearthly (The Unearthly Series)

The Unearthly (The Unearthly Series) The Damned (The Unearthly Book 5)

The Damned (The Unearthly Book 5) The Coveted (The Unearthly #2)

The Coveted (The Unearthly #2) The Vanishing Girl

The Vanishing Girl Death (The Four Horsemen Book 4)

Death (The Four Horsemen Book 4) Rhapsodic (The Bargainer Book 1)

Rhapsodic (The Bargainer Book 1) The Curse Catcher (The Complex Book 0)

The Curse Catcher (The Complex Book 0) The Emperor of Evening Stars (The Bargainer Book 3)

The Emperor of Evening Stars (The Bargainer Book 3) The Forsaken

The Forsaken The Queen of All that Dies (The Fallen World Book 1)

The Queen of All that Dies (The Fallen World Book 1) Dark Harmony (The Bargainer Book 3)

Dark Harmony (The Bargainer Book 3) Blood and Sin (The Infernari Book 1)

Blood and Sin (The Infernari Book 1) A Strange Hymn (The Bargainer Book 2)

A Strange Hymn (The Bargainer Book 2) The Queen of All That Lives (The Fallen World Book 3)

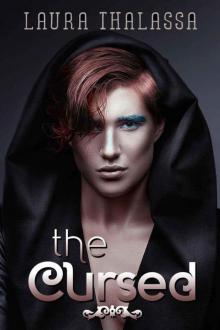

The Queen of All That Lives (The Fallen World Book 3) The Cursed (The Unearthly)

The Cursed (The Unearthly)